Quiz Answer Key and Fun Facts

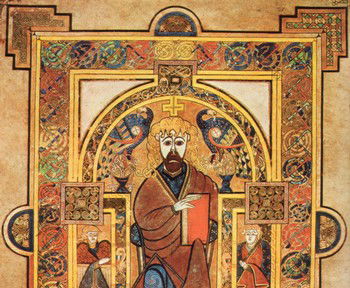

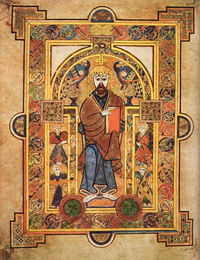

1. Ireland - Book of Kells - c. 800

2. Ethiopia - Mary and Christ diptych - 15th century

3. Greece/Spain - Disrobing of Christ - 1579

4. Armenia - Noravank monastery relief - 13th century

5. Syria - Christ with paralytic - c. 235

6. Byzantine Empire - Christ Pantocrator (St. Catherine's Monastery) - 6th century

7. Italy - Plague crucifix - 11th century

8. Rome - Magi sarcophagus - 3rd century

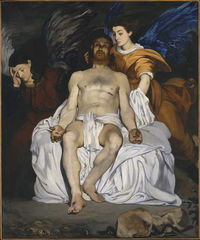

9. France - Death of Christ with Angels - 1864

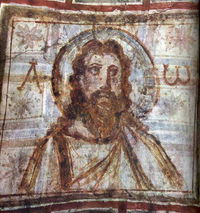

10. Rome - Catacomb mural - 4th century

11. Byzantine Empire - Gold solidus - c. 705

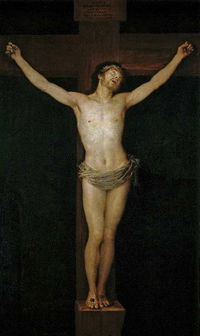

12. Spain - Christ Crucified - 1780

Source: Author

etymonlego

This quiz was reviewed by FunTrivia editor

looney_tunes before going online.

Any errors found in FunTrivia content are routinely corrected through our feedback system.