In the sweltering heat of 1799, a squad of

soldiers stumbled upon something extraordinary while fortifying Fort Julien, a defensive position near the

in Egypt. Embedded within an ancient wall being demolished in the town of

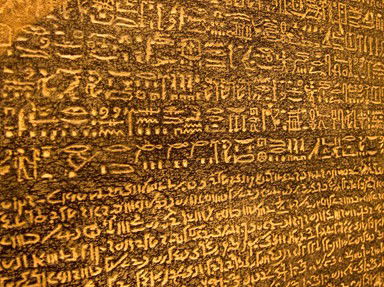

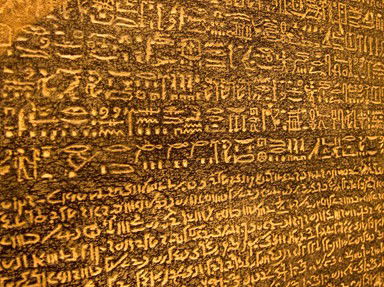

, they unearthed a

slab of dark coloured, slightly

stone, inscribed and mysterious. The stone itself was made of

, a speckled rock often mistaken for

, its darker cousin.

This stone, later named after the town itself, bore a decree written in

distinct scripts. The topmost section displayed the sacred symbols of

, the ancient Egyptian writing reserved for temples and tombs. Beneath it ran the cursive lines of

, the everyday script of the Egyptian people. And anchoring the bottom, in crisp, familiar letters, was

, the language of philosophers, scholars, and bureaucrats.

The decree honoured a young ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty: Ptolemy V, whose name echoed through the stone's scripted proclamation. Issued by

in Memphis to affirm his divine status, the decree was a political tool, but for future

, it would become a linguistic breakthrough.

Why was the

text so crucial? Because scholars could already read it, giving them a foothold into the other

mysterious tongues. The stone became a cypher, a bridge, a linguistic time machine. The decipherment took decades.

First came

, a polymath who made critical progress in the early 1820s, identifying that the

, oval frames in the hieroglyphic text, enclosed royal names. He correctly deciphered some phonetic values and proved the scripts were related.

Then entered

a brilliant linguist with an obsessive passion for ancient Egypt. Building on his predecessor's foundation and armed with patience, intuition, and a gift for Coptic, the last stage of the Egyptian language, he made the final breakthrough in 1822. He cracked the full code of hieroglyphics, the ornate writing system that had baffled minds for centuries.

Today, it resides in the British Museum in

, where millions gaze upon its surface, marveling at the moment when silence gave way to speech.