Quiz Answer Key and Fun Facts

1. A lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), this man argued one civil-rights case after another, but his earliest and best-known successes related to education. In 1967, he became an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, the first non-white person to serve as one of the country's nine top jurists. Who was he?

2. Here's a woman who turned her nightmare into a force for change. When her fourteen-year-old son, Emmett, was lynched, she demanded that the country face up to his murder in all its horrific detail. The memory of Emmett, and the courage of his mother, helped end the culture of lynching. Who was she?

3. This 37-year-old father of three served as Mississippi field secretary for the NAACP, working toward the desegregation of state universities, organizing boycotts, and supporting other civil-rights workers like Clyde Kennard. He was assassinated in the driveway of his own home in June of 1963. Who was he?

4. On December 1, 1955, a middle-aged woman sat down on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama -- and when a white man demanded she give up her seat, she refused. Her arrest drew local action and national attention to deeply unjust segregation laws in the South. Who was she?

5. A co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), this man pursued a strategy of nonviolent resistance to segregation, starting with a sit-in at a Chicago diner and leading right through the Freedom Ride of 1961. Who was this man, who later served as Assistant Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in the Nixon administration?

6. This man, a Quaker, was an early leader in the civil rights movement, helping to organize the Journey of Reconciliation - the very first Freedom Ride - in 1947. He often contributed behind the scenes, advising leaders from James Farmer to Martin Luther King - partly because his enemies tried to use his homosexuality to discredit the movement. Who was he?

7. Raised in Chicago, this woman was shocked by the segregation she experienced when she went to Nashville, Tennessee for college. Studying methods of nonviolent civil disobedience from James Lawson, she helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and co-led a successful campaign to desegregate Nashville's lunch counters. Who was she?

8. All this Army veteran wanted were his rights as a citizen, including access to the education offered by the state. His efforts to enroll at the University of Mississippi required a Supreme Court ruling, 500 U.S. marshals, and additional troops from the National Guard, Border Patrol, and military police. What was his name?

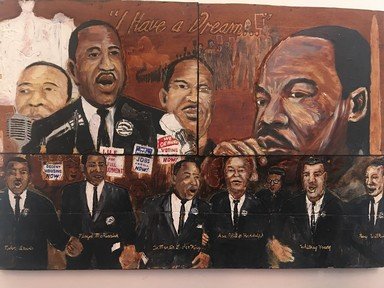

9. The son of sharecroppers, this man was a college student when he decided to help overthrow oppression by means of nonviolence. As one of the original freedom riders, he faced terrible violence; as a march leader in Selma, he was badly beaten by Alabama state troopers. And then, partly thanks to his effort, times changed, and he was elected to Congress in 1987. What's his name?

10. The Civil Rights Movement had many faces, but this man's was foremost among them. He organized, he orated, he marched. In word and in deed, in a speech at the Lincoln Memorial and a letter from a Birmingham jail, he made a powerful moral case for equality -- until he was cut down by an assassin in 1968. Who was he?

Source: Author

CellarDoor

This quiz was reviewed by FunTrivia editor

bloomsby before going online.

Any errors found in FunTrivia content are routinely corrected through our feedback system.