Quiz Answer Key and Fun Facts

1. SS Edmund Fitzgerald leaves from a dock in Superior, Wisconsin.

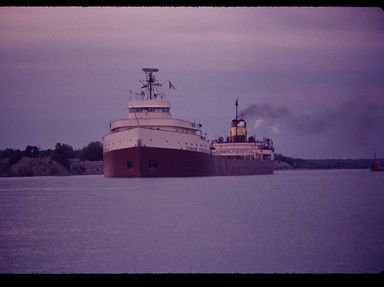

2. The Fitzgerald spots the SS Arthur M. Anderson.

3. A fierce snow whites out the appearance of the Fitzgerald. Except on radar, it is never seen again.

4. The Edmund Fitzgerald tells the Arthur M. Anderson she has taken damage.

5. The storm peaks around Caribou Island; Arthur M. Anderson logs hurricane-force winds as high as 58 knots (107 kmh, or 67 mph).

6. Captain McSorley tells the Arthur M. Anderson, "We are holding our own".

7. The USCG begins its efforts to find the Edmund Fitzgerald after receiving a second call from the Arthur M. Anderson.

8. The USCG search and rescue ship Woodrush arrives at the search area.

9. The location of the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald is officially confirmed.

10. Gordon Lightfoot releases "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald".

11. Coast Guard regulations are updated to require "survival suits," which prevent hypothermia, in crew cabins and workstations.

12. The church bell rings out thirty times at the Mariner's Church of Detroit.

Source: Author

etymonlego

This quiz was reviewed by FunTrivia editor

stedman before going online.

Any errors found in FunTrivia content are routinely corrected through our feedback system.